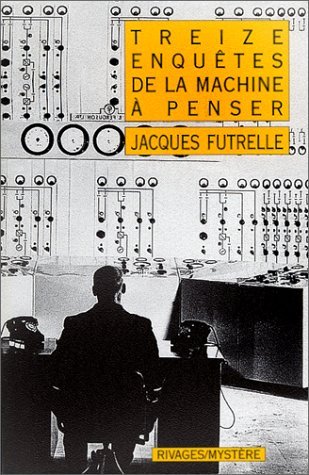

One of those digital discoveries is Jacques Futrelle and his Thinking Machine stories. Rediscovery would be a better word as I already knew both the creator and his creature for having read a sample of their output via Roland Lacourbe's excellent French-language anthology Treize enquêtes de la Machine à Penser. They made a more than favorable impression upon me and I was eager for more, but alas those thirteen stories were all that was available in French at the time, and my English was not yet good enough to allow me to read Futrelle in the original language. Besides, most of his stories were out of print and not easily available. I moved on to other, more recent writers but kept an eye on Amazon and other purveyors in the hope that someone reprints the whole Van Dusen canon.

Fast forward fifteen years and nearly all of Futrelle's output is available for free or very cheap in the Kindle store. I bought a Thinking Machine megapack and started to read, one story at the time, a little afraid not to be able to recapture my initial enthusiasm. I needed not worry: the stories I had read were as good as I remembered them, and the other were for the most part very pleasant surprises.

What amazed me and still amazes me most is how well the stories have aged - probably because they were ahead of their time in many respects. The plots are imaginative and clever if sometimes far-fetched and play fair with the reader at a time when it was not yet a requirement. They also use a lot of misdirection, which is another unusual feature in pre-Trent detective fiction. This is not to say that Futrelle saw his stories as a duel of wits between him and the reader, but neither did he think of them as pure exercises in ratiocination - he was out to puzzle and fool, not just lay down a problem and then provide an explanation.

Another modern feature of his work, perhaps the one that keeps it fresh after all those years, is the writing, which is much less stilted than that of his contemporaries, especially British ones. Being a journalist by trade Futrelle knew how to tell a gripping story with a few words and without excessive flourish. This kind of writing, which John Dickson Carr would call "journalese", would become a distinctive feature of the American school of crime fiction, regardless of the subgenre and may have been a leading factor in its global success and influence on the long run.

Finally there is the Thinking Machine, Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen himself. Futrelle may have created him partly with his tongue in his cheek, as Van Dusen like Poirot later exhibits some physical features (the size and shape of his head in particular) that were bigger than life even then. Still, he is a memorable character and one of the best detectives of his time. Modern readers may find him unlikeable, but so were many of his colleagues at the time - readers then didn't seek to relate to a fictional detective but to be awed by him, and Van Dusen certainly delivers in that department. It is interesting to compare him with the other great detective scientist of the time, Freeman's Dr. Thorndyke - both share an encyclopaedic knowledge and near-universal expertise but Van Dusen has a more abrasive temper and speaks in a much less ornate way. Also, Van Dusen tend to rely less on arcane knowledge than Thorndyke's.

The only serious problem with Futrelle, and one he sadly couldn't fix, is that he died too soon to reach his full potential. Had he not embarked on the Titanic he might have gone to even greater things and maybe dramatically hastened the evolution of American crime fiction. Be that as it may, he remains of those few writers who gave its country a distinctive voice at a time when most of his fellow-compatriots contended themselves with channeling Conan Doyle.